History of Holy Trinity

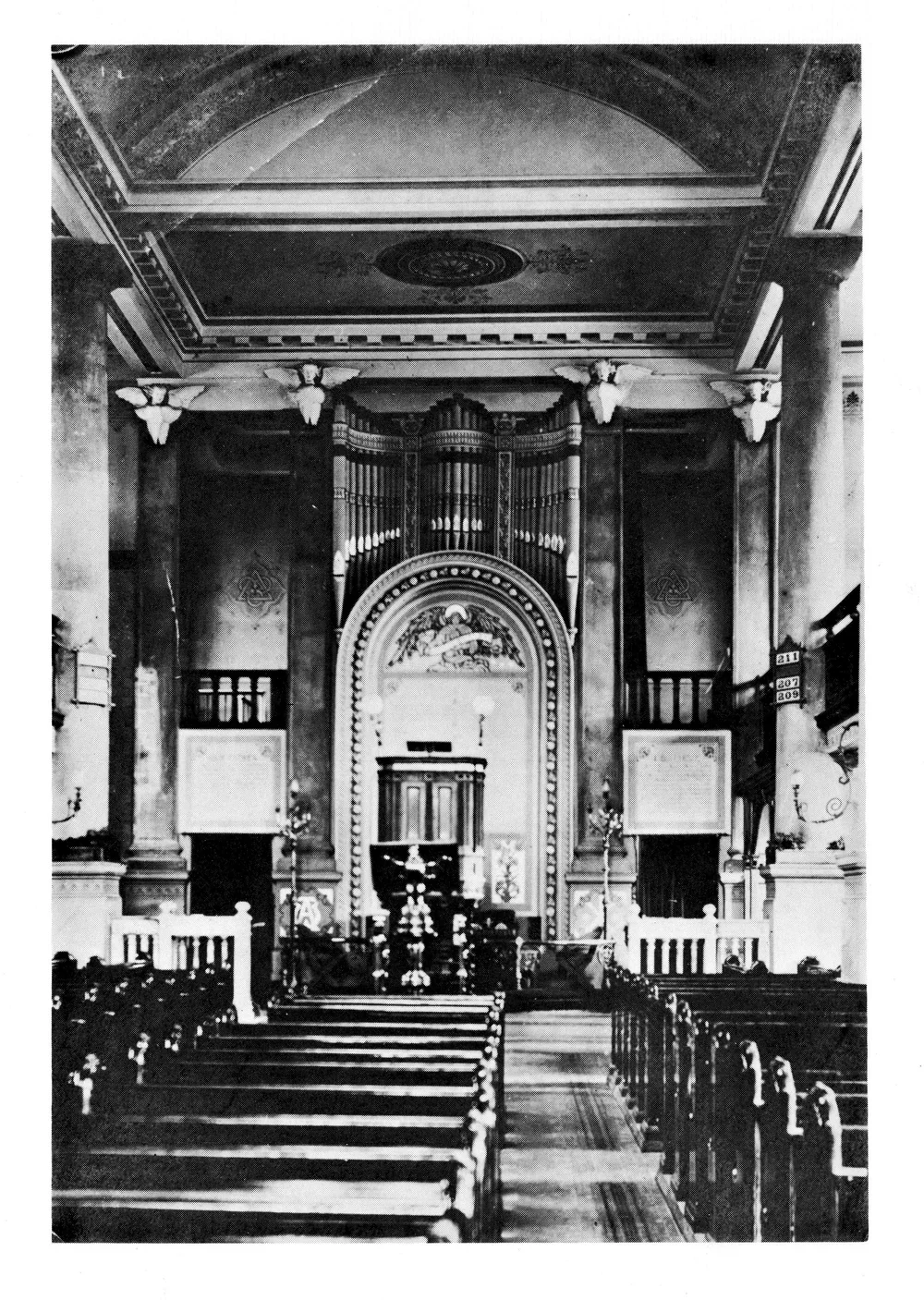

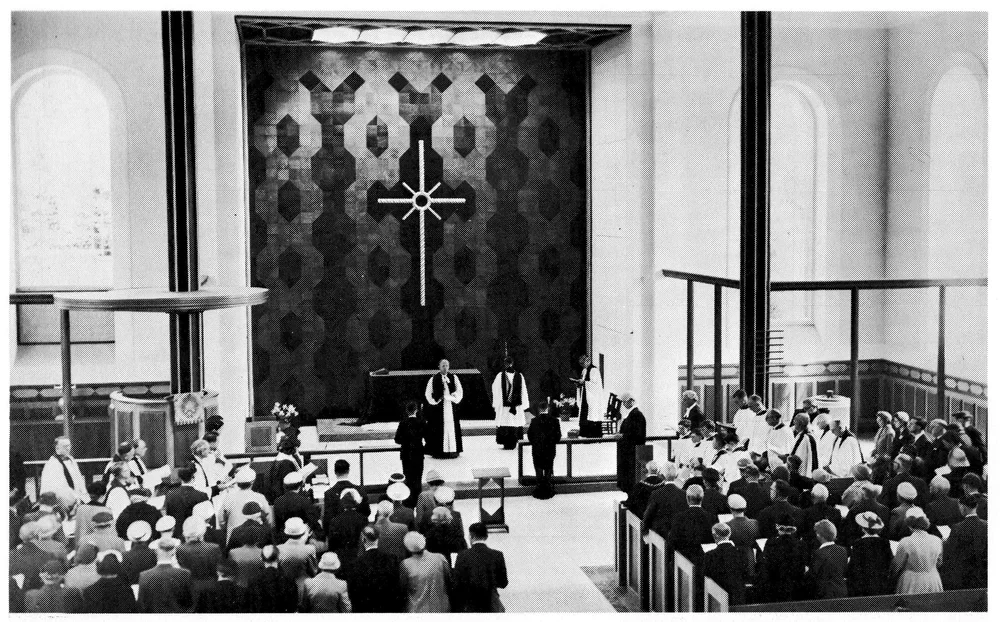

The original interior

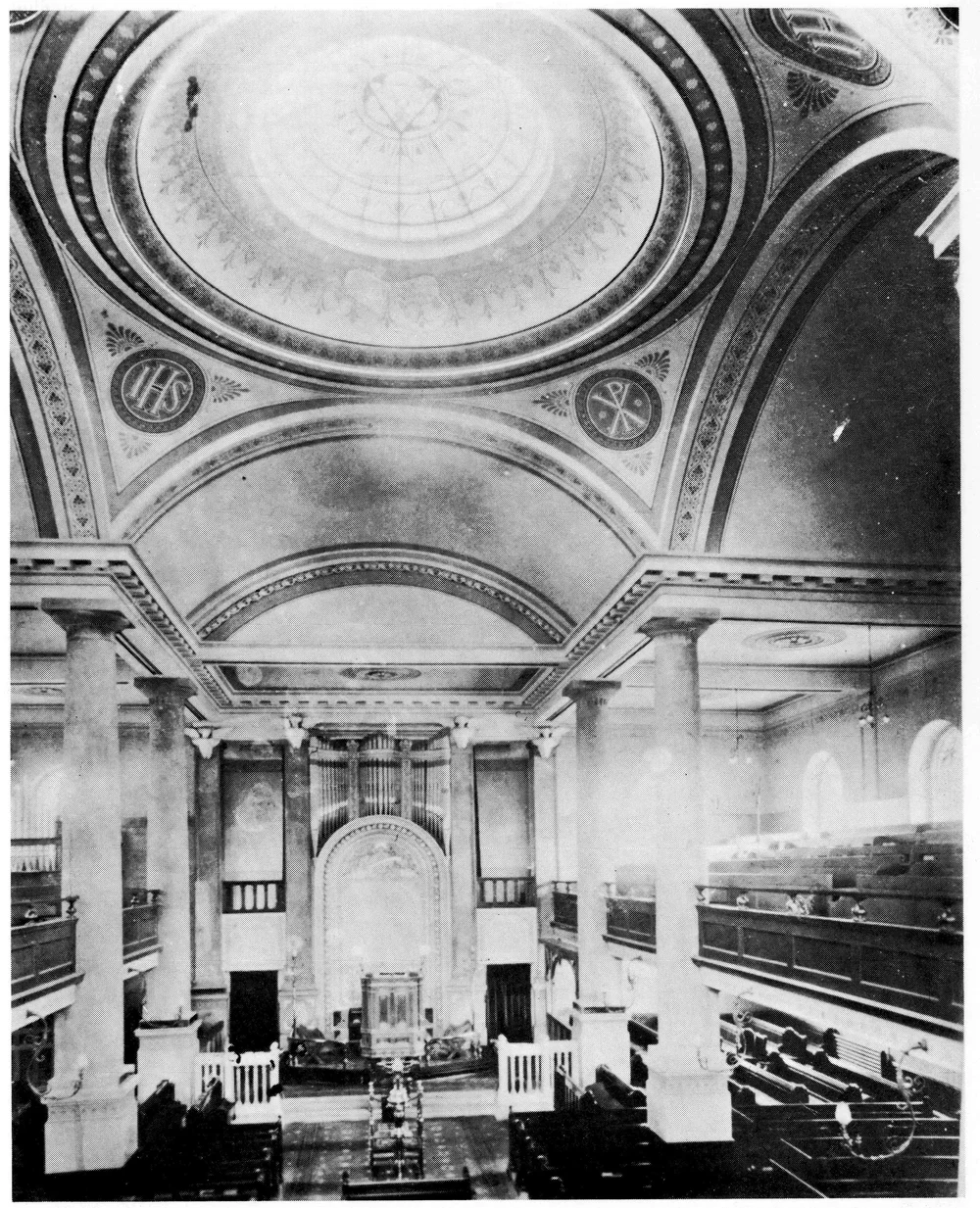

Original interior showing wide galleries and a beautiful dome.

How it all began…

Industrial growth in the 19th century led many people to move from the countryside to cities. In Clifton, the population grew from 4,500 in 1801 to 10,772 by 1826. However, the local parish church, St Andrew’s (including the Dowry Chapel, built for visitors to the Hot Wells), could only seat 2,317 people.

A report from a committee in 1827 highlighted the problem, noting that over 8,000 residents had no access to public worship in the established church. They warned that this lack of religious involvement could lead to “vice and disorder.”

To solve this, they proposed building a new chapel that could hold 1,800 people. Half of the seats would be free, unlike the usual rule where only a fifth were free and the rest were rented or sold to pay the minister.

Fundraising was led by Mr. Thomas Whippie, who donated the land and £4,000. Friends of the first minister, Rev. John Hensman, contributed the remaining £4,000. The chapel was designed by Professor Charles Cockerell, a leading expert in Classical and Renaissance architecture.

The foundation stone was laid on May 18, 1829, and the church was consecrated on November 10, 1830, by Bishop Copleton of Llandaff on behalf of Bishop Gray of Bristol, in front of 2,000 people.

Holy and Undivided Trinity

Originally, the church extended all the way to the West door on Clifton Vale, which is now the entrance hall. Four pillars held up the roof and galleries, which ran along three sides of the church and were built in tiers.

The gallery at the West end reached back to the second set of pillars. The choir sat in the South side gallery, and the organ was first placed at the East end, above the clergy vestry and behind the altar. The pulpit stood in the centre, raised 8 to 9 feet high, as preaching was the main focus of services at that time.

Adaptations to the building and changes within the Parish

Starting in 1830, the original Clifton parish was split into eight church districts to serve the growing population. Along with St Andrew’s and Holy Trinity, new churches were built:

St John the Evangelist (1841)

Christ Church Clifton (1844, became the main parish church in 1940 after St Andrew’s was bombed)

St Paul’s (1845)

All Saints Clifton (1868)

St Andrew-the-Less (1873, near Dowry Square)

St Peter’s in Cliftonwood (later demolished in 1938 and merged with Holy Trinity and St Andrew-the-Less)

Over time, several changes were made to the church building:

Two small doors were added at the West end to ease crowding; they’re still visible but were sealed in 1979 when the current church hall was built.

In 1881, the large West gallery was made smaller. At that time, around 600 people attended morning services, and 550 came in the evening.

In 1887, two more clock faces and three bells (named Love, Joy, Peace, and Hope) were added to mark Queen Victoria’s Jubilee.

Between 1920–1923, a new Sanctuary was built, and the pulpit was moved to the side. This reflected a shift in focus from preaching to the Holy Table, influenced by the Tractarian movement.

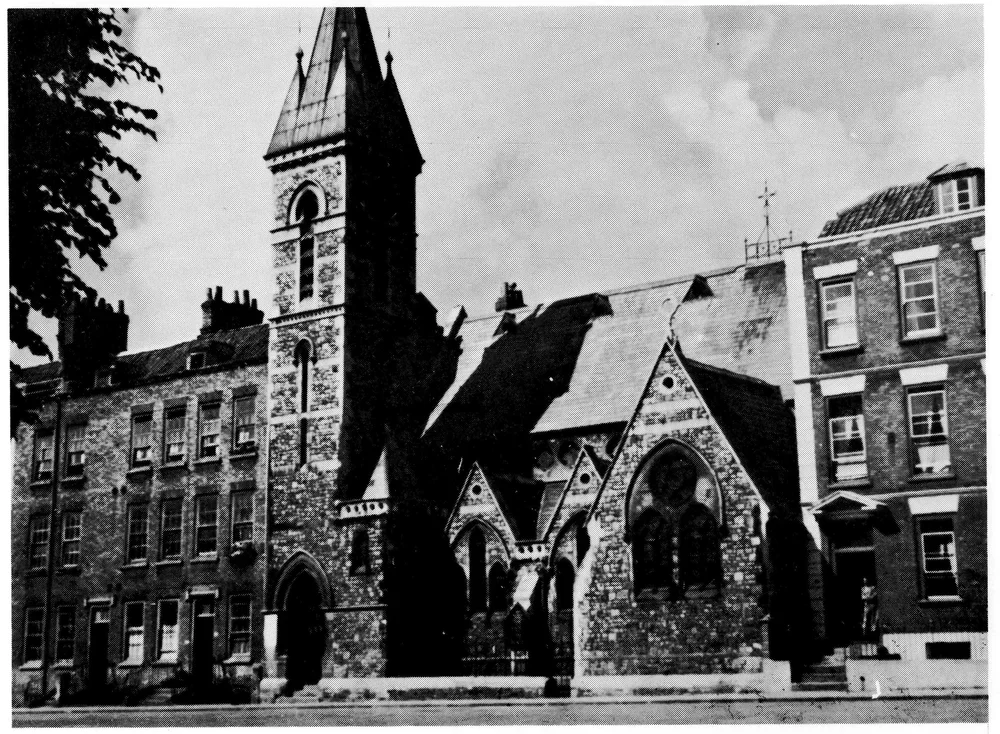

St Andrew the Less Church

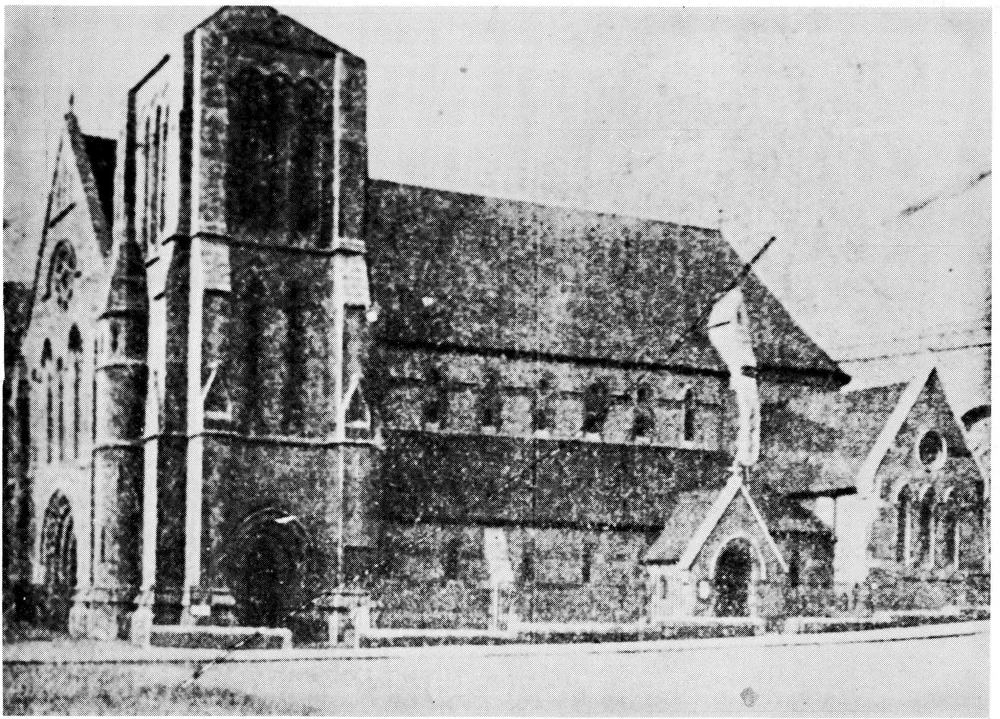

St Peter’s Church, Clifton Wood

After the war, it was decided to rebuild Holy Trinity. The cost was around £60,000, mostly paid by the War Damage Commission, with the rest raised by the public. T.H. Burroughs was chosen as the architect, as he saw Holy Trinity as a priority.

The original walls were kept as a memorial to the original architect, Professor Cockerell.

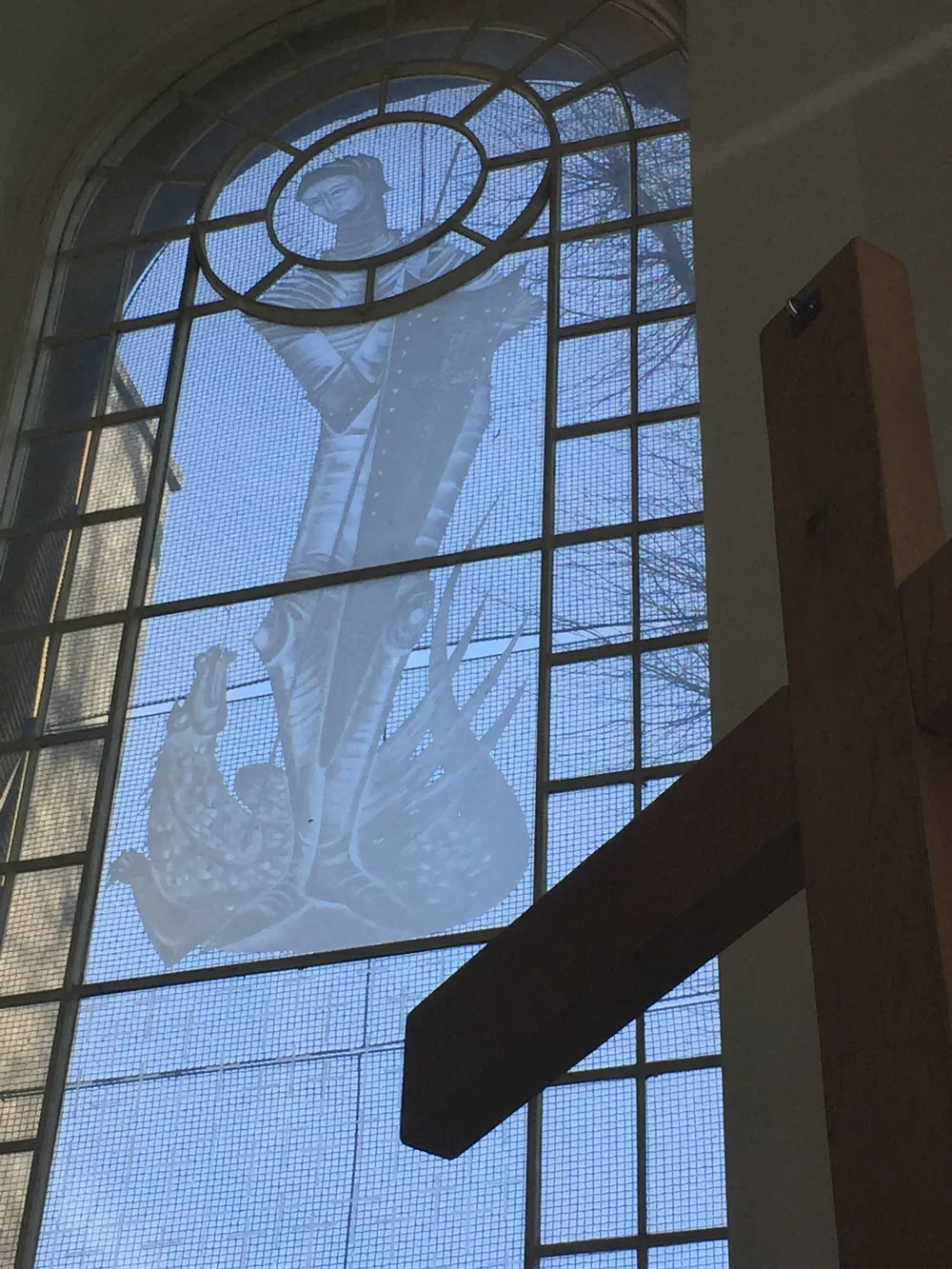

The East windows were replaced with two engraved glass memorials (in the Lady Chapel and Baptistery) by John Hutton, who also worked on Coventry Cathedral.

One of four bells was lost. The other three were melted into a new bell with the words: “I have arisen”, tuned to C major, and weighing 8 cwt.

Only one gallery was rebuilt—at the West end—where the organ console is still located.

The dome was rebuilt in a rare elliptical shape, contributing to the church’s Grade II* heritage listing.

The East end was finished with cork tiles.

Nautical Design Features:

The new design included maritime-themed decorations:

Plaster mouldings copied from ship ropes decorate the dome and cross.

The pulpit was shaped like a crow’s nest.

The font cover resembles a compass.

In 1965, a new window was installed above the South door to block a draught. A dove on the outside wall symbolizes the Holy Spirit.

The Blitz and rebuilding

On the night of January 3–4, 1941, Holy Trinity Church was hit by incendiary bombs. The interior was destroyed, but the outer walls survived. Some items like the lectern, brass cross, and vases were saved.

Services were first held in nearby church rooms on Merchant Road (since demolished), until St Andrew-the-Less, which had closed in 1940, was reopened for use.

Interior 4th January 1941 after destruction by fire. Note the eagle lectern in rubble. The eagle was remounted and is still in use today.

Interior 4th January, after destruction

Modern Alterations:

In 1978–79, the old Merchant Road church rooms were sold, and a new church hall with rooms and toilets was built inside the church using those funds.

Later, a bequest from Mr. Bert Sayer helped add a glassed-in office and meeting room on the balcony.

Original post-war pillars are still visible in the church hall walls. Above them, the ceiling is inscribed with:

Alpha and Omega at the back (symbols for beginning and end)

IHS (Greek abbreviation for Jesus) and XR (Greek for Christ) at the front

More Recent Changes:

In the 1990s, the altar rail and choir stalls were removed, and the sanctuary platform extended to allow more space for musicians. The pews were rearranged for a more relaxed feel.

In 2005, the church was closed temporarily when asbestos was removed from the dome, which required scaffolding and then full restoration.

And Finally…

Holy Trinity Church was built to meet the needs of a changing community. Hotwells, once a wealthy middle-class area, became a strong working-class neighbourhood, with many people working at the docks.

By 1918, the church could no longer rely on pew rents for income. These were ended, and the minister’s pay was then covered by the national church and private donations.

As the docks declined and many buildings were either demolished or turned into homes, the church has adapted. The church hall is now used for worship and also for community events, like the Trinity Lunch Club and the West Bristol Arts Trail.